Along the Caribbean coastline, from Puerto Obaldía in Panama to Capurganá just across the border in Colombia, families arrived exhausted after journeys that had begun thousands of miles away. Some carried children feverish from the heat; others sat quietly, hollow-eyed and unsure what waited next.

Just past the shoreline, mobile care units worked in a constant rhythm. People arrived with blistered feet, sunburned skin, and the exhaustion of long days spent traveling on foot and by boat—carrying large bags with all they could take with them. Doctors of the World staff moved quickly but gently, treating wounds, offering water, and providing brief mental health counseling in the short window they had, often less than a few hours before people had to move on. Every encounter was fleeting, but the need was immense.

These were the scenes of a new kind of migrant flow. After years of record crossings through the perilous Darién jungle, northbound movement has slowed—and in some areas seen a reversal. Tightened U.S. border policies and challenging conditions in Mexico, marked by increased enforcement, overcrowded shelters, and rising violence, have left many stranded or heading back south, their hopes replaced by fatigue and fear.

A joint report by the governments of Colombia, Panama, and Costa Rica, with support from the UN human rights office, found that more than 14,000 migrants—mostly Venezuelans—travelled south between January and August 2025 after being stranded in Mexico and blocked by new U.S. border restrictions. The report warned that people returning home continue to face dangers, including violence, extortion, and sexual assault, with limited humanitarian protection, as many aid groups were forced to suspend operations due to aid cuts.

A joint report by the governments of Colombia, Panama, and Costa Rica, with support from the UN human rights office, found that more than 14,000 migrants—mostly Venezuelans—travelled south between January and August 2025 after being stranded in Mexico and blocked by new U.S. border restrictions. The report warned that people returning home continue to face dangers, including violence, extortion, and sexual assault, with limited humanitarian protection, as many aid groups were forced to suspend operations due to aid cuts.

Along the Colombia-Panama border, Doctors of the World health workers describe rising cases of trauma among returnees. “Many people have had to leave behind everything—or the little they had managed to build—to return to their home country,” said Jesús Chacón Ibarra, a nurse working in the region. “It deeply affected their mental health. We saw cases of anxiety, sleeplessness, loss of appetite, and in some cases, people say they feel lost.”

A survey of returning migrants conducted in March 2025 showed the risks for women remain alarmingly high: nearly half reported experiencing sexual violence, often under the guise of “searches” for hidden belongings.

The migration routes cut through some of the most isolated and under-resourced areas in the region. Puerto Obaldía, a coastal town in a remote indigenous region spanning the Panamanian Caribbean, is one of the main landing points for migrants returning to South America. After days of travel by land and sea, often in overcrowded boats with no protection or life jackets, migrants arrive sunburned, dehydrated, and physically exhausted.

Health workers said they’ve treated cases of malaria, respiratory infections, gastrointestinal illnesses, and skin conditions linked to exposure and poor hygiene. Doctors of the World teams—comprising two doctors, two psychologists, and a nurse—have provided primary care, mental health support, and sexual and reproductive health services to migrants and members of the host communities.

The cross-border initiative, supported by the European Union and conducted in partnership with HIAS, has reached more than 50,000 people across Colombia and Panama—over half of them women and girls—providing medical care, psychosocial support, and protection along one of the world’s most dangerous migration corridors.

Yet, as the need for care shifts, humanitarian funding is being cut back, forcing many organizations to reduce or suspend services.

Facing Uncertainty in Mexico

Across migrant hubs in Tapachula, Tabasco, and Mexico City, tens of thousands of migrants face an uncertain future as they navigate shrinking options and difficult decisions about what comes next. Increased border restrictions and immigration enforcement have slowed migration north, halted asylum claims, and left tens of thousands of migrants in limbo across the country. Mexican officials have been moving migrants away from the northern border to southern cities like Tapachula and to Mexico City, part of a broader strategy to discourage crossings and reduce pressure along the border.

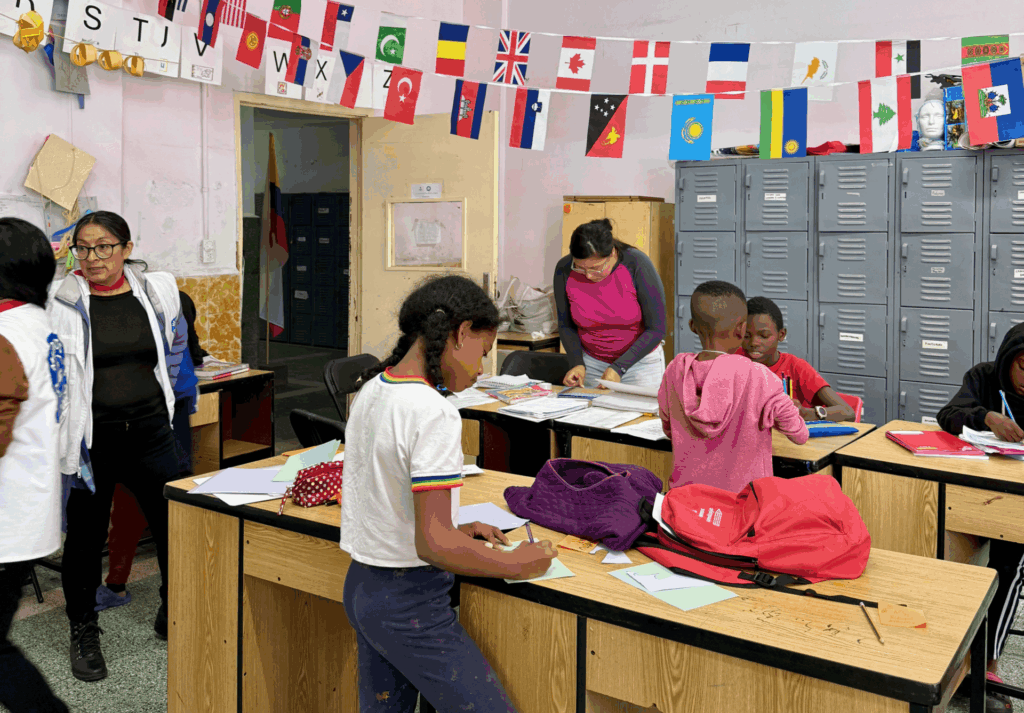

In Mexico City, Doctors of the World operates clinics across informal camps and shelters, providing basic healthcare, mental health support, and protection services even as other aid groups have scaled back. Much of the population here consists of families, including single mothers and fathers with children.

The team visits four shelters—both government-run and faith-based—and the Refugee Agency office in Iztapalapa each week. Many migrants are reassessing their options, with some planning to return home and a growing number applying for asylum in Mexico; many come from Haiti, Cuba, Central and South America, and West Africa.

On a recent site visit, our Executive Director, Fraser Mooney, spoke with families navigating these uncertainties, including Maya, a pregnant woman from Colombia, who was receiving a consultation from one of the clinic’s doctors. Her journey began in November 2024 near Bogotá, alongside 15 family members. Together, they crossed the perilous Darién Gap, encountering the bodies of migrants who had died along the way. From Panama to Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, and Guatemala, the family moved north to Mexico, often stopping along the way to earn money to pay extortion demands or government fees.

Today, Maya is waiting in Mexico City, unsure what comes next. Doctors of the World arranged emergency cash transfers through a partnership with Save the Children to help her cover basic needs as she prepares to give birth far from home.

Today, Maya is waiting in Mexico City, unsure what comes next. Doctors of the World arranged emergency cash transfers through a partnership with Save the Children to help her cover basic needs as she prepares to give birth far from home.

With tens of thousands of migrants facing an uncertain future and little access to food, safety, or support—and with aid funding running dangerously low—the risks of abuse and neglect continue to grow. Yet amid this uncertainty, Doctors of the World continues to create small but vital spaces of care: places where trauma is met with compassion, and where dignity has a chance to take root again.

Colombia photos and stories courtesy of Médecins du Monde Colombia/Alejandra Ramírez Ochoa

This story is part of Safe Spaces for Care, Doctors of the World USA’s year-end campaign highlighting frontline voices at the heart of crisis and displacement. Through mobile clinics, local partnerships, and global advocacy, Doctors of the World creates safe spaces where families can find healing and be seen—wherever they are. These lifelines rely on continued support in the U.S. and around the world to ensure access to care for those who need it most.